Some places never leave you. They settle deep in your bones, shaping the way you move through the world. For me, that place has always been the water.

Some places never leave you. They settle deep in your bones, shaping the way you move through the world. For me, that place has always been the water.

I was born in Key West, the daughter of a Navy man, and the ocean was my first home before I even knew how to name it. My earliest memories drift between places—Eleuthera, Bahamas, where the water was so clear that fishing boats hovered above the reef like ghosts, their shadows rippling over the sand; Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, where the waves stormed the shore, swallowing the sand in great frothing surges, only to draw back and gather their strength for another charge.

Then, the moving stopped. And so did my family.

When my parents split, my brother and I were sent north, far from the turquoise waters, to live with our grandparents in upstate New York.

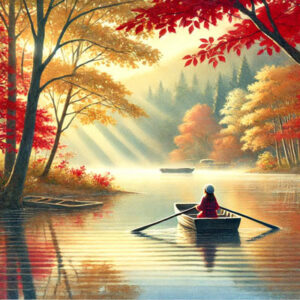

Saratoga Lake was nothing like the ocean, but it became my world. The water lay deep and still, its surface broken only by the ripple of my oars, the hush of mist curling in the morning air. In autumn, the trees along the shore ignited in a blaze of red, orange, and gold, their reflections painting the lake in perfect symmetry, the colors so rich it felt like rowing through fire.

The legend was as much a part of the lake as the mist that rose at dawn. The Mohawk people had warned that Saratoga’s waters belonged to the Great Spirit, that a careless voice—a single word—could shatter its peace and summon its wrath. Those who disturbed the stillness would find their canoe upturned, the dark water swallowing them whole.

Whether it was truth or only a story meant to keep travelers quiet, I never knew. But I believed in the lake’s silence. When I rowed, I moved without a sound, my paddle slipping through the water like a whisper. It wasn’t fear that kept me quiet, but reverence—the feeling that something unseen hovered just beneath the surface, listening, waiting.

In winter, the pines stood heavy with snow, their branches bowed under the weight of ice. Beyond them, the Adirondack Mountains rose and fell like frozen waves, their peaks lost in morning mist. The lake itself was a mirror, smooth and unbroken, stretching between the trees like a window into another world.

We’d lace up our skates and dare each other toward the center, where the ice was thinnest, where the wind cut our breath short and the cold burned in our chests like swallowed frost.

Spring loosened winter’s grip. The ice cracked and split, breaking apart in jagged sheets that drifted toward shore. The mud swallowed my boots as I waded along the banks, cupping frogspawn in my hands—delicate, transparent things, somehow strong enough to outlast the freeze.

By summer, the lake was alive again. I swam until my fingers wrinkled, until my hair smelled of earth and water, of weeds and sun-warmed stone. The scent clung to me, settling into my skin like memory.

I spent hours outside, alone but never lonely. The woods, the water, the wind—they were my constants. And the birch trees, my only friends. I’d row out to them, their white trunks luminous against the dark forest, whispering all my secrets into their peeling bark, trusting them to keep what the world was too loud to hear.

On the outside, I blended in—laughing when expected, speaking when required. But inside, an ache lingered, steady as the tide against the shore. I longed for what was lost, for a family that no longer fit together as it once had. So I sought solace in the quiet places—among the trees, on the water—where I didn’t have to explain, only exist.

Even in college, I was drawn to the trails, letting the steady cadence of my footsteps quiet the noise inside me. And when I returned to Florida, hoping to reconnect with my father, I found myself near the water once more.

Nature has a way of calling you back, revealing truths you didn’t know you were searching for—if only you stop long enough to see them.

Maybe that’s why I write about nature. Not because I planned to, but because I don’t know how to stop.

Because, in the end, we always find our way back to the places that made us.

~ L.S.